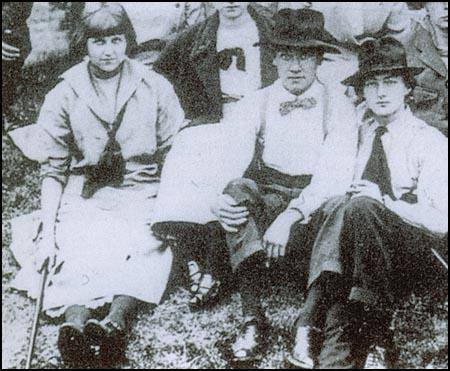

What interested me most about the writings of Virginia Woolf were the various radical portrayals of women; no woman was completely comprised of a single characteristic, or “creed” of identity. We’ll never know for certain who exactly inspired her female characters. But there is little doubt there were plenty to choose from among her radical circle. One that caught my attention particularly was Dora Carrington, an artist and member of the Bloomsbury group that came to work for the Woolfs’ publishing press with her husband Ralph Partridge during the period in which Mrs Dalloway was being written. Already well-known to Woolf due to her devoted companionship with Lytton Strachey (one of Woolf’s closest friends) they became firm friends. Woolf was intrigued by Carrington and documented with fond fascination the goings-on of her unorthodox lifestyle. Perhaps she sensed a kindred spirit. Carrington flew in the face of convention in every way possible in her personal life. Woolf’s writings fiercely upbraided the restrictions society imposed upon women, barring them from developing their true characters. Carrington’s complicated relationship with her own femininity and her guarded manner relating to her artwork depict someone who might well have been a heroine in one of Woolf’s novels.

Carrington’s attitude to her femininity was mixed. To begin with, she went to some lengths to cast off a traditional feminine visage- in 1911 she took the drastic step of cutting her long hair in the style of a pageboy crop. It was an open declaration of revolt (Gerzina, 28) and the beginning of a lifelong courtship with an androgynous appearance. The object was simple-making her gender secondary to herself. She went a step further with her admittance in a letter to her then-lover Mark Gertler that she “hated being a girl” (Gerzina, 45). Her initial fear of sexual relations further emphasizes her inner turmoil over her identity as a woman. Gertler’s relentless attempts to persuade her to lose her virginity to him, coupled with pressure from the Bloomsbury group who assisted him in this venture, were repulsed fiercely by Carrington. Her naivety as a consequence of her upbringing in a Victorian home and her passion for freedom contributed to her view that such pressure on her was an attempt to assert ownership (Gerzina, 303). Woolf’s own tentative attitude to sexual relations seems to mirror those of Carrington’s-most likely she would have sympathized with Carrington’s predicament. Mrs Dalloway is full of connotations that imply marriage and the sexual relations that follow as a form of male assertion of ownership. Hugh’s forceful attempt to kiss Sally to recompense her daring to disagree with him in public recalls Carrington’s fear of sex as a physical violation. Similarly, Carrington’s allusions in her letters to her own bisexuality when referring to an encounter with a female friend, “I longed to possess her in some vague way” (Gerzina, 184) are oddly reminiscent of Clarissa’s confusion over her feelings for women “she did undoubtedly feel what men felt [for women]” (Woolf, 26). Thus, Carrington’s tumultuous relationship with her femininity reflects the restrictions of the society in which she lived, and such conflicted portraits of women Virginia Woolf was all too apt at portraying in her work.

Another crucial part of Carrington’s identity was her role as an artist. She was clearly an artist of outstanding ability, and it has long been in dispute why she remained in the shadows while other Bloomsbury artists touted acclaim for their endeavours. David Garnett particularly accuses Strachey and Partridge of not taking Carrington’s artist ambitions as seriously as they should have done (Elinor, 31). Michael Holroyd disputes this strenuously in his biography of Strachey, insisting that he always expressed his admiration and encouragement of her work (Elinor, 31). Whatever the case, Carrington did confess to feeling intellectually inadequate whilst in the company of the “Bloomsburies”; she even confessed to feeling “stupid and hopeless about [her]self” (Elinor, 31). However, while she did not publicly exhibit her work, a compilation of her work arranged by her brother Noel Carrington brought her talents to light. What was remarkable about Carrington’s work was her ability to transform a project of domesticity, such as the designs of her own homes in Tidmarsh and Ham Spray, into an expression of her own artistic prowess. Her apt hand at landscape is reflected in her combination of the sublime and banal; the swan designs on the windows carry a distinctly romantic element, and the oranges of the building also lend a touch of the exotic. However, this is balanced by the cool blue and green of the sky and field that encompasses it. Her unique vision of creating her own ideal space within a conventional domestic sphere might not evoke radical artwork in its assumed terms, but that she does so is innovative and clever, changing convention to suit her. One can only imagine how coveted Carrington’s work may have been in her lifetime had it been made public. Mrs Dalloway also reflects on how ambition has been cherished and yet inevitably been pushed to one side for the sake of the domestic through Clarissa, Peter, and Sally. Clarissa abandoned Peter, Sally and “all those plans” for the security offered by Richard Dalloway-and she is not without regret. It rears its head when she meets Peter once more, and reflects on how different her life could have been had she married him and pursued what they had once dreamed of. Perhaps Woolf was considering her own fellow female members of Bloomsbury and an anxiety for them to exercise their full potential.

Carrington’ eventual suicide, borne of grief over the death of Strachey, was deeply distressing to Woolf-particularly as Woolf had been the last person to speak to her before she died. She expressed a relief and gratitude to being alive, little realizing she herself would take the same tragic course of action years later. However, Woolf and Carrington’s artistic endeavours stand aloft from their tumultuous personal lives-almost “a room of one’s own”, the sphere where society did not oppose or oppress them, but allowed full expression of the self.

Dora Catrington At Slade School. Google Images. <http://spartacus-educational.com/ARTnevinson.htm>

Virginia Woolf. Google Images. <http://www.independent.co.uk>

Elinor Gillian. “Vanessa Bell And Dora Carrington: Bloomsbury Painters”. Women’s Art Journal Vol.5 No.1. News Brunswick: Women’s Art Inc, 1984. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1357882>

Gerzina Gretchen. Carrington: A Life. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1989.

Glass Ensemble By Dora Carrington. Google Images. <http://www.pinterest.com>

Portrait Of Tidmarsh House. Google Images. <http://paintingdb.com>

![20160203_104339[1]](https://rfitzgeraldsite.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/20160203_10433911.jpg?w=614&h=346)

![20160228_201448[1]](https://rfitzgeraldsite.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/20160228_2014481.jpg?w=760)

![20160228_190133[1].jpg](https://rfitzgeraldsite.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/20160228_1901331.jpg?w=760)